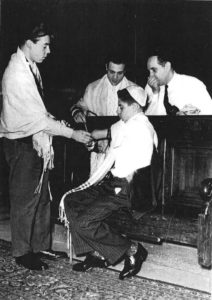

Courtesy of Joyce de Botton

“In every generation,” we read during the seder, “a person must regard himself as though he personally had gone out of Egypt, as it is said: ‘And you shall tell your son in that day, saying: “It is because of what the Lord did for me when I came forth out of Egypt.””

For most Jews sitting down to seder with their friends and families, this is a difficult proposition, one that frequently inspires discussion.

What does it mean to regard oneself as having been redeemed from bondage in Egypt? Can such a thing even be done?

But for a few families, the instruction to regard themselves in that way is hardly theoretical; it’s family history, something that happened to them or their parents in living memory.

Locals like Albert and Toni Algazi, Jocelyne Balcher, Rabbi Albert Gabbai of Congregation Mikveh Israel and Joyce de Botton each left Egypt between 1956-1970 under intense pressure from the government, or worse. They were forced out, or they left in the cover of night, with only what they could carry. They were driven from Cairo and Alexandria and ended up in Philadelphia, where the yearly commandment holds special meaning.

“When we do the Haggadah every year, and we sit down and we read, it does bring some memories from Egypt,” Albert Algazi said.

Albert Algazi, 72, and his sister, Jocelyne Balcher, 61, lived in Cairo with their mother, Toni Algazi, 95. Today, Albert Algazi splits time between Yardley and Florida, Balcher calls Langhorne home and Toni Algazi lives at a senior living community in Voorhees, New Jersey.

Toni Algazi was the daughter of a Syrian Jewish father, a tailor, and an Italian Jewish mother, who stayed home with the family. They spoke Arabic and French in the house, and attended the Sha’ar Hashamayim Synagogue.

“In Cairo, it was beautiful,” Toni Algazi said. “I can’t deny that it was beautiful. Little by little, it changed while we were there. We did not realize and then it was dangerous.”

Albert Algazi was just shy of 18 when his mother and father woke him early on Feb. 2, 1966, and told him to hurry to the limousine waiting outside. In a quiet moment, he looked out from the balcony and realized he was looking out at Cairo for the last time.

The limo took the family to Port Said, packed with all they could fit, including a Torah and the pittance of their savings that they were permitted to take. They boarded a ship for Marseille, France, where Toni Algazi had family. Stateless and without passports, the family stayed in France until August, when they left for Trenton, New Jersey, where Toni Algazi’s husband, Charles, had a brother.

Joining them on that panel was Gabbai, a native of Cairo who remembers a flourishing, cosmopolitan Jewish community, rife with civic associations and economic opportunity. His father was born in Baghdad, and his mother in Italy, making Gabbai a first-generation Egyptian. They spoke French, Italian and English at home, and enough Arabic to navigate the grocery store.

But it wasn’t to last.

“There was no future for the Jews in Egypt,” Gabbai said.

He was in high school when the Six-Day War began; this was when Gabbai and his three brothers were taken to prison camps. They would remain there without trial, charges or legal representation until 1970.

After international pressure, Egypt released Gabbai and his brothers, who were flown to Paris. Gabbai stayed there for about a year before he came to New York, where he’d remain until moving to Philadelphia in 1988.

His life in Egypt and his subsequent detention come to mind each year at Pesach, and he’s blunt on the subject.

“I don’t have to pretend,” Gabbai said. “I lived it, OK?”

He’s never been back to Egypt, and doesn’t plan to return.

For de Botton, born to a well-off family in Alexandria, the pandemic was a time to reflect on her journey to America. Her family’s experience of Egypt was far from bondage, an experience she recounts in a self-published book that she created for her family over the last year, “Nana’s Story: From Egypt to America.” De Botton describes a life in Alexandria filled with parties, loves won and lost and meringue at the Sporting Club.

After the Suez Crisis in 1956, her husband, Claude de Botton, decided that he wanted to leave Egypt, to return to his studies at the University of Pennsylvania. She mourns the life she’d left behind, and still feels angry about what she lost.

The early days in the United States were difficult, but the family eventually found success on the Main Line, and de Botton is proud of their lives here and elsewhere; through her husband, she is related to the famed Swiss writer, Alain de Botton.

“I have lived the American Dream!!” she wrote.

[email protected]; 215-832-0740