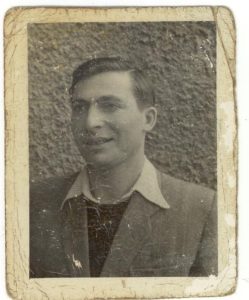

Joseph Gringlas, who survived the Blizyn, Auschwitz and Mittlebau-Dora concentration camps, died Nov. 8. He was 96.

“He had the courage to create life, live life and enjoy life,” daughter Marcy Gringlas said from Jerusalem, where her father was buried. “He was my true hero.”

Born in Ostrowiec, Poland, Gringlas grew up as the youngest of six children of Lazar and Blima Gringlas. His father worked as a shoemaker.

The German army invaded Poland on Sept. 1, 1939, and occupied Ostrowiec a week later. Food soon was rationed, and Lazar Gringlas was not permitted to work, according to a biography by the Echoes and Reflections Partnership based on a 1996 USC Shoah Foundation interview. A ghetto was established in the town in 1941, although the Gringlas family didn’t have to move since their home was inside ghetto borders.

While in the ghetto, Gringlas cleaned the streets, performed manual labor, worked in a kitchen and toiled in a steel mill.

In 1942, most of the family was sent to Treblinka when the ghetto was liquidated — only brother Sol, the family’s only other survivor, stayed behind.

The brothers were later separated, with Joseph Gringlas sent to help build the Blizyn concentration camp. He later was transported to Auschwitz, where he lied about his age and was sent to work at Auschwitz III-Monowitz — and also was reunited with his brother.

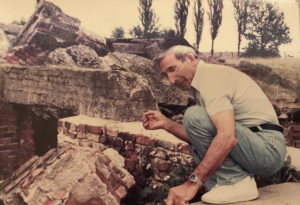

“I will never forget the day I arrived here,” Gringlas told his granddaughter Sara Greenberg in a 2005 Jewish Exponent article about a return to Auschwitz. “When I got off the train, I could see that the sky was red. The permanent smell of burning bodies is something I will never forget. It is a miracle I survived.”

Greenberg produced a documentary called “B-2247, Granddaughter’s Understanding” — her grandfather’s Auschwitz tattoo number — that incorporates footage of that trip, including a visit to Auschwitz.

In several cases, the skills Gringlas learned early in life saved him, he said in a 2018 Exponent article.

“Would you believe in Auschwitz, while they are killing people, the Germans decided they wanted to plant flowers? When I was in Poland, I had learned about flowers. I still like flowers. So I got the job. I got double bread and double soup, so I wasn’t so hungry anymore. What happened [is that] a lot of people came and stepped on the flowers. Thousands of people came through, and they stepped on the flowers. They ruined the flowers. But what am I going to do? People are going to be gassed.

“The next morning the [guard] comes and says, ‘You see what happened? The only thing you have to do is take a stick and hit them over the head!’ But Joe wouldn’t do it! No! Because you’d never believe it, but a lot of people behaved like that. I wasn’t raised like that. I said, ‘No, sir.’ If he had been a bad [guard] he could have killed me. But what he did was took away my double bread and double soup. But I didn’t care.”

The brothers endured the Death March from Auschwitz in 1945, ending up at Mittlebau-Dora. They were liberated by the United States Army on April 11, 1945, although not before being injured by shrapnel, which Joseph Gringlas carried in his lungs for the rest of his life.

Those days before liberation were harrowing, as the brothers endured Allied bombings, fleeing the barracks and hiding amid kitchen pipes to survive. They learned that the SS guards murdered anyone in the barracks who survived the bombings.

“I weighed 80 pounds. I was running,” he said in the 2018 Exponent article. “I was excited — I never thought I would get out of there.”

Joseph and Sol Gringlas — who died in May 2020 at the age of 100 — lived at the Landsberg Displaced Persons Camp after the war, where the former attended technical school before immigrating to Detroit in 1950 and owning a television repair business. He moved to Philadelphia in 2008.

“He struggled, and he worked hard and had his own life and his own business,” Marcy Gringlas said. “It was never easy.”

Gringlas spoke often to school groups, where teachers asked him why he wasn’t bitter about his experience.

“He was the opposite of bitter,” Marcy Gringlas said, noting that her father learned that carrying around bitterness would only hurt him.

Gringlas debuted as an artist in 2018 at the age of 93, displaying his watercolor and oil paintings at Haverford College’s Visual Culture, Arts and Media Center through the Stories that Live fellowship program of the Rohr Center for Jewish Life Chabad House.

Gringlas is survived by his wife of 64 years Reli, who is also a survivor; daughter Marcy (Joel Greenberg); son Larry (Karen Fink); five grandchildren; and one great-grandchild.