This year feels a lot like 1970 for those who remember it.

Memories of a controversial war with consequences felt in the United States and a divided country is unwelcome for those who experienced the beginning of the Vietnam War and the series of Marches on Washington, where waves of people gathered to fight for civil rights.

The past weeks have stirred up more memories than some of these elders had bargained for.

After Politico published on May 2 the 98-page Supreme Court draft by Justice Samuel Alito that would overrule the 1973 case of Roe v. Wade, Americans pored over the document, some applauding, others taking to the streets to express their discontent with the majority opinion.

The Jewish community was well–represented among Americans in protest of the decision, which would return the power to restrict access to legal abortion to the states, almost imminently resulting in the ban of abortion in the South and Midwest U.S., and potentially in Pennsylvania.

According to Senior Rabbi Daniel Burg of Beth Am Synagogue in Baltimore, the new law of the land would interfere with his interpretation of Jewish law, which deems abortion permissible, as the life of the pregnant parent takes precedence over the fetus.

“Each of us is created in the image of God, which has infinite value. Each of us is responsible for our bodies, to treat them with high regard, and to treat one another, as far as bodies, with high regard,” Burg said. “That big takeaway from that is that we need to respect the sovereignty of each person’s bodies with regard to behaviors that are acceptable, according to Jewish law.”

Burg, a Reform-trained rabbi at a Conservative synagogue, is not alone in his belief. The Orthodox Union published a statement criticizing the Supreme Court ruling, claiming that restrictions on abortion would prevent the ability to protect the gestational parent’s life, violated the Jewish principle of pikuach nefesh, saving a life. The organization, however, did not fully condemn the case and stated that it did not advocate for “abortion on demand.”

On May 17, Burg and congregants, as well as dozens of other Jewish organizations, will take to the streets once more at the Jewish Rally for Abortion Justice in Washington, D.C.

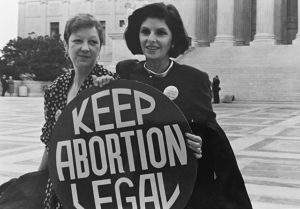

Though the march will take place only weeks after the draft leak, it has been decades in the making, with activists from half a century ago laying the groundwork for the country’s next round of fighting for abortion access and providing insights on how the movement could look moving forward.

But the conversation around Roe v. Wade really begins before the 1973 decision, Philadelphian Carol Daniels, 73, claims.

The landmark court case was nestled in a period of history where women’s rights were still precarious and when college students found power in protest, not voting, which, at the time, was only permitted for those 21 years and older. Wite-Out was one of the more revolutionary technologies of the time.

“The way we had our voices heard was not through the internet; it was not through cell phones,” Daniels said.

Matriculating to New York University in 1966, Daniels lived in a dorm where men and women were separated; women had an 11 p.m. curfew and had to sign in every night before bed.

Her sophomore or junior year, student protesters tore down the wall between the gendered dormitories, which eventually resulted in the school creating co-ed dorms. Daniels attended the March on Washington in 1969 and opposed the Vietnam War.

“We had our lives on the line,” she said.

Though her time in college was marked by the civil rights era and the Vietnam War, the Kent State Massacre, when members of the Ohio National Guard opened fire and killed four and injured nine Kent State University students in 1970, changed her world.

College campuses, much like in spring 2020, shut down. Daniels graduated from NYU in 1970 pass-fail.

In August 1970, women’s rights had taken center stage in the country. Daniels traveled to Washington for the Women’s Liberation March led by Gloria Steinem and Betty Friedan. The march did not explicitly address abortion access but began to open the door for women to speak about their bodies more openly, to talk about and understand sex, which was stigmatized at best and demonized at worst.

“Everybody was called a ‘whore’ or a ‘lesbian’ who participated in that march,” Daniels said.

At the same time as the Boston Women’s Health Book Collective published “Our Bodies, Ourselves” in 1970, an anatomy book written “by women for women” to help open dialogue around sex and biology, Daniels had an abortion in New York, one of the four states where abortion was legal at the time. It was expensive, and her boyfriend at the time refused to help pay.

In other areas of the country, women were not as lucky as Daniels.

Liz Downing, now the vice president of advocacy of the National Council of Jewish Women of the Greater Philadelphia Section, had friends who had back-alley abortions in the same era. The use of coat hangers — now a symbol used by abortion access advocates — left some friends injured and others unable to bear children.

According to Downing, this wasn’t unusual: “People knew people knew people.”

Organizing protests was a grassroots effort of meeting friends in their living rooms, hoping people would check their mailboxes or pick up their landline telephones when protest plans were in motion.

But even after the decision of Roe v. Wade, victory for abortion access activists was short-lived, with the 1992 Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pennsylvania v. Casey case, which originated in Pennsylvania, all but overturning Roe v. Wade.

Before the case was presented in front of the Supreme Court in 1992, Kol Tzedek synagogue member and health care lawyer J. Kathleen Marcus worked as a lawyer for the case when it went to District Court, when she was a “little baby lawyer, minutes post-bar exam.”

On the district level, the plaintiffs, including Planned Parenthood, argued against the commonwealth to deem five provisions, which included women having to get the consent of their male partner to get an abortion, unconstitutional. The plaintiffs won the case with the help of Marcus, 59, who discovered that one of the “mental health experts” the commonwealth brought to testify on their behalf had, instead of a doctorate in psychology, a degree in home economics.

“That led to this wonderfully detailed decision, where Planned Parenthood won every single aspect, except [declaring parental consent for abortion unconstitutional],” Marcus said. “And so that was a near-perfect win.”

When the case went to the Third Circuit Court of Appeals, however, the District Court decision was partially reversed. Marcus remembers reading the decision confused and frustrated by the author. It was written by then-Circuit Judge Alito.

By the time the case reached the Supreme Court, the five original provisions from the Pennsylvania government were upheld. Planned Parenthood v. Casey effectively overturned Roe v. Wade, Marcus argued.

“In a sense, that was even more insidious because it allowed for very restrictive state laws to be passed that have, since ‘92, essentially eliminated abortion in a huge swath of states,” she said.

Years later, Marcus signed an amicus brief for a Louisiana case that banned abortion. The brief was signed by women lawyers and law students who had received abortions — the beginnings of a growing trend of people going public with personal experiences of having an abortion.

“There are a number of things on the ‘choice’ side that have changed, and one is the willingness of people to come out and say, ‘I had an abortion, and I’m not ashamed, and here’s my story,” Marcus said.

In the past few years, celebrities such as Phoebe Bridgers, Uma Thurman and Stevie Nicks have shared their abortion stories online, which Marcus believes is a powerful tool.

But social media, which activists have used to catapult mobilization efforts and rally protesters on short notice, is a double-edged sword, Downing said. It’s also a place to witness vitriol and misinformation.

“There was a time of broadcast news, which I miss very much, which required that there be opposing sides,” she said. “So I remember really appreciating the fact that, when there was an issue that was considered controversial, the news media were responsible for providing both sides of the argument.”

Daniels shares Downing’s ambivalence toward social media, favoring face-to-face conversations. She hopes to facilitate an intergenerational dialogue in order to inform the younger generation — hungry idealists in her eyes — about her own experiences. The conversations, in turn, help to wash away some of the jaded feelings Daniels has, watching history repeat itself half a century later.

“It does give me hope,” Daniels said. “Because you have foot power, and I really believe that you have voting power; you have your physical power, your mental power, and you have a desire to think about your future.”