Jacob Gurvis | JTA.org

Throughout an illustrious 72-year career as a newspaper reporter, Jerry Izenberg has just about seen it all.

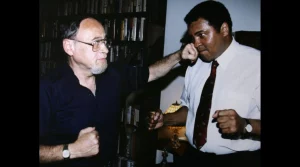

The longtime columnist for The Star-Ledger in Newark, New Jersey, Izenberg covered the first 53 Super Bowls. He’s been to 58 Kentucky Derbies, not to mention numerous Olympics, World Cups and boxing matches. He considered Muhammad Ali a close personal friend.

But the fiery 92-year-old, who still contributes to the paper as a columnist emeritus from his home in Nevada, doesn’t approve of the term “journalist.” He’s a newspaperman.

He dropped the name of Samuel Pepys, the 17th-century British diarist, as a contrast.

“Every day he took his big diary, and he wrote what he did this day, what he was planning to do later — that’s a journalist,” Izenberg said. “I’m not in my world. I’m in the world of other people trying to interpret and to repeat what values they have or what lack thereof they have.”

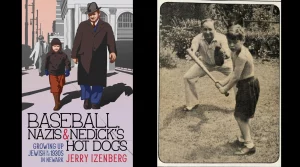

Izenberg’s latest story breaks that rule. His 17th book, which recently hit shelves, is a memoir about his Jewish upbringing in Newark. Titled “Baseball, Nazis, and Nedick’s Hot Dogs: Growing Up Jewish in the 1930s in Newark,” the memoir centers on Izenberg’s relationship with his father Harry, a World War I veteran and former minor league baseball player.

Izenberg’s father emigrated to the United States as a child, leaving Lithuania with his family to escape anti-Jewish pogroms. As his sportswriter son recounts it, Harry discovered baseball even before he could speak English.

The Izenbergs’ love of baseball transcended all. When Jerry got his first baseball glove at 10 years old, it was a milestone that in his father’s eyes surpassed even his bar mitzvah.

“He had given me a lifetime gift — a simple game and a simple shared love for it,” Izenberg writes in the memoir. “It remains there, bright and shining in memory eighty-three years later.”

The pair’s passion for baseball was closely intertwined with their Judaism. Growing up in Newark in the 1930s and ‘40s, Izenberg was a fan of the New York Giants baseball team. They featured a lineup filled with Jewish players: Harry Danning, Harry Feldman and Sid Gordon.

But in the pantheon of Jewish baseball during Izenberg’s childhood, there was a clear king, and — much to the chagrin of Izenberg’s father — he played in Detroit. Hank Greenberg, the greatest Jewish hitter in baseball history, was at the peak of his Tigers career from 1935-1940, winning two most valuable player awards on his way to the Hall of Fame.

At the Izenbergs’ dinner table, there were only a few select topics discussed: baseball and the Nazis.

In 1938, Greenberg was chasing Babe Ruth’s single-season record of 60 home runs, which Ruth had set in 1927 with the Yankees. Greenberg would ultimately reach 58 homers, while drawing several walks in the season’s final games.

“My dad was convinced that was antisemitism,” Izenberg said. “And I said to him, later on when I got into the business and I knew people, ‘Did it ever occur to you that the guys who pitched against him didn’t want to be the guy who threw his 60th home run ball? They’d be linked to him forever.’ My father said, ‘That’s an interesting theory, but you’re full of crap.’”

Of all the anecdotes Izenberg shares about his father, one non-sports-related scene stands out.

One Saturday in 1939, Izenberg and his father went to the Newsreel Theatre in Newark, where audiences gathered to watch news and sports highlights of the week. That day, the theater showed footage of the infamous Madison Square Garden rally held by the German-American Bund, the American Nazi organization.

Izenberg remembers leaving the theater with his visibly angry father. His father talked about how the Nazis — or, as he called them, mamzers, Yiddish slang for “bastards” — had to be stopped.

“I’m an 8-year-old kid, and I say, ‘But dad, they’re in Germany,’” Izenberg recalled. “And he looks at me, he says, ‘They’re not in Germany, they’re here.’ And he was right.”

Despite the anti-Jewish sentiment that was ever-present in his youth, Izenberg said he has not faced antisemitism in his journalism career. As a columnist who has covered just about every sport, Izenberg has received his fair share of criticism — most notably having his car windows smashed by two men who did not approve of Izenberg’s defense of Muhammad Ali when the boxer stirred controversy by supporting the Nation of Islam and refusing to enlist in the military.

Izenberg has written about social issues often throughout his career — especially race relations — a tendency that he said is inspired by the value of tikkun olam. It’s an idea he learned from Rabbi Joachim Prinz, the activist leader who spoke just before Martin Luther King Jr. at the 1963 March on Washington.

After leaving Nazi Germany, Prinz settled in Newark, on the same block as the Izenbergs. He would become a close family friend and even offered to help Izenberg prepare for his bar mitzvah, even though his family belonged to a different synagogue.

Izenberg said he is guided by tikkun olam, “because I know [Prinz would] want me to keep it in the back of my mind, and my father would, too.”