Kurt Leo Schoen was a Holocaust survivor who didn’t call himself a Holocaust survivor.

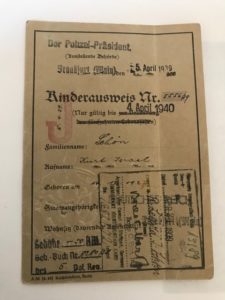

He fled Nazi Germany in 1939 at age 11 before ever setting foot in a concentration camp.

But while Schoen avoided the worst years of Nazi Germany, he could never escape the experience of living under it.

Like many Holocaust survivors, Schoen used his appreciation for life as motivation to focus on the important things and achieve success. He built a family with three children. He also became a patented food flavor chemist at David Michael and Co. in Philadelphia, according to family members.

Through it all, he focused intensely and daily on his kids. After being separated from his sister and father during their respective passages to the United States, Schoen made sure to arrive home in time for dinner every night as an adult. His advice to his children was always to appreciate their opportunities in life.

Schoen died on Feb. 24. He was 94.

The Philadelphian is survived by his children Marcia Cherry, Michael Schoen and Karen Schoen; four grandchildren; his sister-in-law Alice Schoen and nieces, nephews and their families.

“He had a good, long life,” said Marcia Cherry of Dresher. “He truly did a lot, despite the rough beginning.”

“He did everything he wanted to do,” Karen Schoen said.

Schoen was born on Dec. 14, 1927, and grew up in Kassel, Germany, according to Schoen’s 2002 oral history interview with the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C. His father owned a shoe wholesale and retail business. His family lived in a mixed neighborhood, including non-Jews, and attended a local synagogue.

“Everything was fine until 1933,” said Schoen in the oral history interview.

That was the year when Hitler was appointed chancellor of Germany and later made himself the rule of law.

Shortly thereafter, Schoen’s father was forced out of his store by a boycott; Schoen was no longer allowed to associate with non-Jews; and the young boy often had things thrown at him, both objects and profanities, by other kids.

Schoen’s sister got to the United States first, in the late 1930s, with help from a group of Jewish women in the U.S., according to the oral history. Then his father received an affidavit, or a pledge of financial support, from family members in New York City. By 1939, Schoen was able to escape with the rest of his family.

Schoen’s sister got to the United States first, in the late 1930s, with help from a group of Jewish women in the U.S., according to the oral history. Then his father received an affidavit, or a pledge of financial support, from family members in New York City. By 1939, Schoen was able to escape with the rest of his family.

In the U.S., according to the notice, he learned English, served in the Army and earned bachelor’s and master’s degrees from City College of New York and the Brooklyn Polytechnic Institute, respectively. He “proudly married Berta Cooper Schoen” and moved to Philadelphia to launch his career.

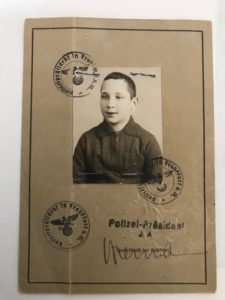

(Courtesy of Michael Schoen)

Cooper Schoen, an American from Connecticut who died in 2016, balanced out her direct and often brutally honest husband, according to Cherry.

“If he thought you were doing something wrong, he had no problem telling you,” she said.

Later in life, Schoen didn’t talk much about his childhood. But at times, it would come up.

When Cherry was in college, she hosted a friend at the Schoen house. The friend’s father was German, and after he came to pick his daughter up, Schoen told Cherry that the man reminded him of the kids who used to throw rocks at him.

Another time, Cherry’s piano teacher gave her a song to play. But Schoen couldn’t listen to it. It reminded him of Germany.

“It haunted him a little,” Cherry said.

But the experience also molded Schoen into a man who pushed his kids to work hard.

They went to Hebrew school three times a week plus Shabbat services. They had to get jobs in their teens. And “it was assumed we would go to college,” Cherry said.

But more than anything, the kids remember their father being there. At 5:15, he walked in from work, according to his daughter. By 5:30, the family was eating dinner.

Michael Schoen also remembers driving to New York and Connecticut to see extended family. These weren’t holiday trips, either. They were just on random weekends.

“It wasn’t typical for my friends. They’d see their families a few times a year,” Schoen said. “For him, it really was a priority.”

Schoen’s family also had a way of bringing out his lighter side. His daughter said he could be very funny. Michael Schoen said he talked to his father every day; they had the same dry sense of humor.

And after Cherry had her own two children, grandpa was always available to run them around.

“He did very well for himself. He has an estate,” Cherry said. “But honestly, family was always first.” JE

[email protected]; 215-832-0740