Sukkot is meant to celebrate the beauty of impermanence, symbolized by the temporary structure under which one dwells.

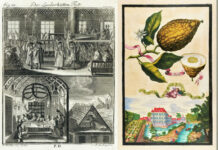

However, after chag, there’s one ritual item — the etrog — that some are reluctant to part with, as its scent is emblematic of the holiday’s rich themes of harvest. It’s also exorbitantly priced.

“You paid $70 for a lemon!” said Gratz College President Zev Eleff, who authored “The History of the Etrog in America,” which appeared in Segula magazine in August.

Perhaps because of its steep cost, or perhaps for sentimental reasons, Jews are turning to creative epicurean ventures to make the most of the citrus following Sukkot.

Though fragrant, the smell of an etrog is a bit deceiving. The fruit is bitter if eaten raw, due to the thick white pith that dominates the inside of the fruit below its delicate and oily rind. If one were to squeeze an etrog and expect juice to flow out of the fruit like a lemon, they would be disappointed.

“You can kind of think of an etrog as a citrus fruit that puts all its energy into fragrance; it’s all about the oil,” Philadelphia-based chef and food writer Aliza Green said.

Yet home cooks and chefs alike have managed to turn the formidable fruit into something delicious anyway, using the pectin-rich pith to create thick and syrupy etrog marmalade.

Green offsets the bitterness of the fruit by slicing it and soaking it in syrup, though etrogim can also be boiled — once in water and again in simple syrup — to candy it.

Greg Kirkpatrick of Lindcove Ranch in Lemon Cove, California, the country’s only commercial etrog grower, suggests a riff on limoncello.

By peeling etrogim rinds and soaking them in the highest proof alcohol available, one can have a fragrant liqueur after about two months of waiting.

Along with the plethora of dishes that can be made with etrogim are the plethora of varieties of the fruit.

According to Green, Moroccan etrogim are preferred by Sephardic Jews and aren’t commonly found in America; the Diamonte variety, popular among Lubavitch Jews, is grown in the Calabria region of Italy.

Yemenite etrogim are the most rotund; Balady, or native, etrogim are grown in Israel; and within the Balady variety, there are Halperin, Braverman and Chazon Ish etrogim, among others.

Green sources many of her etrogim from Lindcove Ranch, which grows five varieties of etrog and is experimenting with a sixth. She deviates from many Jews who prefer to ship in the citrus from Israel, preferring fruit grown for consumption.

In Israel, etrog farms abound, but because the fruit is prone to pests and fungus, chemical interventions must be taken to protect the fruit. If the rind becomes too blemished, the fruit is no longer deemed kosher.

“They’re not really grown to be consumed,” said Rebbetzin Reuvena Grodnitzky from Mamash! Chabad in Center City. “They have a very intense level of pesticides.”

At Lindcove Ranch, however, though some pesticides are used, threats to the etrog trees are thwarted by the growth of avocado trees, which are resistant against fungal growths.

But growing etrogim is no easy feat. Kirkpatrick has worked with local farms to grow the fruit, but there have been 13 failed attempts.

“People just think they can throw seeds in the ground and make a lot of money, but it just doesn’t happen,” Kirkpatrick said.

Israeli etrogim are easier to grow, but it comes at the cost of the etrog’s taste.

Because she sources her etrogim from Israel, Grodnitzky opts to dry out the fruits and use them as besamim for Havdalah. Before the etrogim dry, she and her children, each with their own etrog, pierce the fruit’s flesh with aromatic cloves.

Tova du Plessis, the pastry chef behind Essen in South Philadelphia, takes a similar approach, boiling etrogim with cinnamon stick and sage, or whatever herbs and spices she has in the house. Lavender stems, rosemary, cloves and eucalyptus are popular in her household.

The fragrance of the simmer pot acts like a scented candle, refreshing a space.

“It’s especially useful after cooking a strong-smelling dinner or when having people over,” du Plessis said.

Though not typically edible, etrogim from Israel still have an advantage over their U.S.-grown counterparts, Eleff said.

“As American Judaism embraces Zionism more and more … Jews — Orthodox, Conservative and Reform — are taking on the mitzvah of the etrog, not just because of religious sensibilities, but also because it’s in concert with their Zionist fealty,” Eleff said.

Though Eleff joked about the priciness of etrogim, he was insistent that their lingering beyond the holidays, whether in the form of a snack, drink — or even dried and piled in a bowl in the kitchen — is remarkable.

“In a time in which there’s a lot of questions about continuity and observance, here’s an example of how people try … to extend that meaning,” Eleff said. “The liqueurs and the jams and the like are an example of how we pour our religion into all sorts of spaces.”

[email protected]; 215-832-0741