By Jon Marks

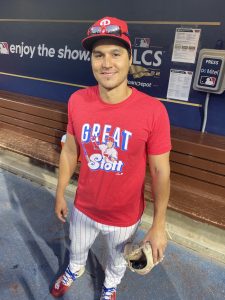

Astute Phillies fans will probably recognize his face. Some might even know his name.

But chances are that none of you have a clue that Diego Ettedgui, the Phillies’ Spanish language interpreter, who does much more than translate what the team’s Hispanic players are saying from Spanish to English, comes from a family with a rich Jewish tradition dating back more than 500 years.

The story of how the 35-year-old Ettedgui, who grew up in Caracas, Venezuela, then came to the United States to study, despite not knowing English, is fascinating in itself. But the saga of the Ettedgui family, who started in Spain, then chose to leave rather than be forced to convert to Catholicism, is legendary.

“My family’s name goes back to a long time ago in Spain,” said Ettedgui, sitting in the Phillies’ dugout before Game 4 of the National League Championship Series, a day before the team punched its ticket to the World Series. “Back then (in the 1492 Alhambra Decree), the Queen (Isabella) wanted everyone in Spain to become Catholic and said to people of other religions, ‘You either convert or you’re out of here.’

“My family was one of those who said, ‘No, we’re not going to become Catholic. We’re Jewish.’ And they moved from Spain to the North side of Morocco in a city called Tétouan.”

Ettedgui’s not quite sure how long they remained in Morocco, but some of the family eventually decided to cross the Atlantic Ocean.

“Somewhere around 1860-‘70, my family moved from Morocco to Venezuela,” said Ettedgui, who joined the Phillies in 2016 at a time when Major League Baseball began requiring teams to have interpreters for its Hispanic players. “They were merchants, selling shoes, soap and other things.”

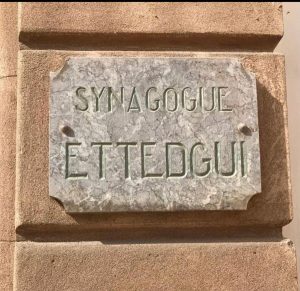

Apparently, those who stayed behind made enough of an impact in the community that a synagogue was built in their name. The Ettedgui Synagogue was built in 1920 in Casablanca.

Courtesy of Diego Ettedgui

It didn’t last long, destroyed during World War II by accident during an Allied bombardment of the city. King Mohammed VI of Morocco rededicated the synagogue.

That’s the story young Diego was told growing up in Caracas, where his great-grandfather, Herman, got him interested in sports.

“He was my role model,” said Ettedgui, who was 19 when his family sent him off to school in Boston at Bunker Hill Community College before he went on to graduate in health management at Northeastern University. “From the day I was born, he pretty much injected sports in our veins (he and his younger sister Ana). He did a lot of things for Venezuela and played soccer, baseball and track and field. He lived ‘til almost 95, and he loved the Yankees, but you’d hope he’d root for the Phillies now.”

Speaking of Bryce Harper, Rhys Hoskins, Kyle Schwarber, Zach Wheeler and company, just how did Ettedgui find his way here to serve as an interpreter?

Going back about a decade, Ettedgui realized health management wasn’t for him and began looking for an alternative. After taking a communications course in Spanish with Colombian radio broadcaster Carlos Cabello, Cabello offered him a chance to do a sports segment on his radio show, then followed up by helping him get a job with El Mundo Boston, the city’s Spanish newspaper.

It wasn’t long before Ettedgui became the paper’s sports editor, covering not only the Red Sox but the Celtics and the Revolution soccer team. That whet his appetite for something more and, in 2016 when baseball mandated interpreters for its Spanish players, Ettedgui went for it.

Naturally, he first went to the Red Sox and was in contention for a job when the Phillies called. The team flew him to spring training in Clearwater, and he impressed them enough to offer him the job. With the Red Sox still undecided, he jumped at their offer and moved to Philadelphia.

Seven seasons later, Jorge Alfaro, Andres Blanco, Odubel Herrera and Freddie Galvis, the Spanish-speaking players who were there when he arrived, are gone. The current group consists of pitchers Ranger Suarez and Jose Alvarado and utility infielder Edmundo Sosa.

While his main duty is translating for the players during interviews and sitting in on pregame strategy meetings with the hitting and pitching coaches to help them understand how to pitch certain hitters or position themselves on defense, there’s a lot more to the job.

“I help out during batting practice,” said Ettedgui, who played baseball and soccer growing up in Caracas, where his school’s biggest rival was Collegio Hebraica. “I catch throws in the outfield and throw with the pitchers, and I’m Seranthony Dominguez’s catching partner.

“During the game, I’m in charge of the pitch coms (the device where the catcher signals the pitches to the pitcher). I give (Manager) Rob Thomson the com when a new pitcher comes in.”

He’s even busy outside the lines: helping players understand contracts, taking them to doctor’s appointments, the bank, car dealerships and public appearances.

And there are times he goes with the Phillie Phanatic to schools.

“They’ve started a Phanatic Reading program in the schools,” said Ettedgui, who became a Spanish citizen last year due to his family’s Sephardic Jewish connection. “When we go to schools where there are Latino kids, sometimes the parents don’t speak English. So when we go to introduce the reading program with the Phanatic, they need that letter to be in Spanish.”

Jon Marks is a freelance writer.