The man who helped create Disney Studios’ golden age was the same man who also helped end it.

Art Babbitt, a Jewish animator for Disney Studios, worked on projects such as “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs”, “Pinocchio”, “Fantasia” and “Dumbo”; he helped develop the character of Goofy.

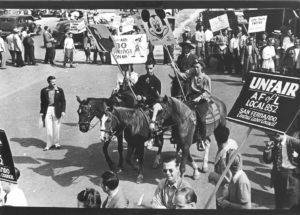

But away from his drawing board, Babbitt was also a union proponent, leading animation artists in a strike against their company and Walt Disney in the early 1940s. Disney Studios was one of the last arts companies in Hollywood to become unionized.

The story in all its complexities is detailed in “The Disney Revolt: The Great Labor War of Animation’s Golden Age” published July 5 by Chicago Review Press. The book was written by Philadelphia native and Jewish animator Jake S. Friedman.

Babbitt’s call for unionization mirrors those of his Jewish predecessors on the East Coast.

“You’ll see time and time again, people who lead like the garment workers union in New York and so on, always appear to be Jews, usually Jewish immigrants,” Friedman said.

Friedman, 41, suggested that Jewish union efforts were the result of the failed promise of a land of greater opportunity and the desire for escaping the oppressive structures of their home countries.

In a time of pervasive unionization efforts across Hollywood, Disney trailed behind the rest. Even in its golden age, the company shrunk its animator employee base from 1,400 to 600 at its smallest. Some animators, the “inbetweeners” who drew the in-between drawings, were given a salary of what would be worth $18,000 today. Animators who worked on large projects like “Fantasia” earned closer to $22,000 adjusted for inflation.

Disney Studios’ revolutionary work betrayed the conflict happening under the surface. Babbitt’s animation style transformed what was believed to be achievable in the art form. Using a form of method acting, Babbitt would study the movement of people he had met as a young person in the streets of New York. He created the “Character Analysis of the Goof,” a treatise digging deep into the mind of the character.

After Babbitt led his co-workers in a nine-week strike, what followed was a battle of public relations, Friedman said. Strikers were called communists, and strikers claimed that Disney was antisemitic.

“This made Babbitt’s martyrdom more personal and gave them justification to antagonize Walt Disney,” Friedman wrote. “It became a battle cry of the strikers, who wanted to punish Walt the way they felt they had been punished.”

The antisemitic claims were lofty; Disney had many Jews in his inner circle, and the accusations emerged during a bitter period after the strike.

Through the telling of the labor dispute within the company, Friedman’s goal was not to paint Babbitt as the hero and Disney as the villain, but rather to tell the fraught story of two people with similarly strong convictions and passion for art with staunchly different political ideologies.

Friedman also has personal ties to the subject of the novel. An instructor of animation history at New York University Tisch School of the Arts, his alma mater, and the Fashion Institute of Technology, Friedman has a passion for the medium. He also has deep roots in labor organizing.

Growing up in Elkins Park, Friedman was shaped by the Jewish educators by which he was surrounded. He attended Solomon Schechter Day School and Akiba/Jack M. Barrack Hebrew Academy, attributing his passion for writing to his English teachers, but continued to be influenced by educators outside of school.

Friedman’s mother, father and grandmother participated in the Philadelphia teacher’s strike in 1973. They all volunteered to get arrested, as striking was illegal, and a photo of Friedman’s father getting arrested appeared in the Feb. 19, 1973 Philadelphia Evening Bulletin. The newspaper clipping was treasured by the family.

“That was as much of my makeup as my Jewish identity,” Friedman said. “Part of my heritage was knowing that I came from strikers who fought for what they believed.”

As much as “The Disney Revolt” is a book outlining a history of a time Friedman was fascinated by, it was written for a broader audience with the hope that anyone, even those without a background or interest in animation and history, could draw inspiration from it. The book is a call to action.

“The Hollywood unions did not happen in a vacuum. There were…all sorts of examples of people who stood up and gathered to fight for what they believed all over the country,” Friedman said. “It’s not an East Coast thing. It’s not a west coast. It’s not a Midwest thing. It’s an American thing. And I want people who read this book, who wouldn’t otherwise be accustomed to that idea, to get a kernel of some information that will encourage them to learn more.”