Natalie Scharf of Northeast Philadelphia, who survived the Holocaust, died on Aug. 1. She was 95.

The Holocaust “decimated her family,” as her parents, Yitzhak and Rasel, and three sisters, Chava, Rivka and Sarah, did not survive.

But Scharf did.

After the war, she married Bernard Scharf and had two children: son, Jeffrey, and daughter, Andie. She also had five grandchildren and three great-grandchildren.

Scharf never stopped thinking about the Holocaust, guilting her children about how ungrateful they were to be in the U.S., and dreaming about her parents — and sometimes waking up screaming.

She also wrote notes on pictures of happy memories, though tinged with residue of the horrors she endured. One said, “Here’s the family enjoying a seder. Who knows when the next one will be?” Another: “Here we are sitting on the balcony in Miami. Who knows when we’ll be here again?”

“There was doubt to whatever she was enjoying,” Jeffrey Scharf said.

In her later years, Scharf got an iPad. According to her son, she primarily used it to research the Holocaust. One time, she even cursed out a Holocaust denier on Facebook.

“She was afraid everybody would forget,” Jeffrey Scharf said.

Scharf’s fear drove her to become a primary source for an upcoming documentary, “My Underground Mother,” about the Gabersdorf labor camp for teenage girls.

The journalist behind the documentary, Marisa Fox, placed an ad in The Canadian Jewish News in 2010 seeking out survivors to share their stories. Cara Scharf, Jeffrey Scharf’s daughter, saw the ad and told her grandmother.

Over the last decade of her life, Scharf talked to Fox over the phone, via email and in person. Her memories will help frame the movie, which is expected to be released in the next couple years.

“She remembered details that others had not,” Fox said. “She was touched that somebody cared.”

Born Natalie Mehlman in 1925, she grew up in Jaworzno, Poland, where her father owned a grocery store.

“They always had food on the table,” Jeffrey Scharf said.

But in 1939, the Nazis defeated the Polish Army and started implementing ominous laws. For instance, Jews weren’t allowed to own stores, walk on sidewalks or eat more than 900 calories a day.

Two years later, Nazi soldiers ripped Scharf, her sister and her mother from their beds in the middle of the night. Scharf begged the soldiers to take her instead of her younger sister; they took both, but sent her sister to a death camp.

“She thought she was saving her younger sister,” Jeffrey Scharf said.

The Nazis sent Scharf to Gabersdorf. While there, Scharf refused to read postcards from her mother, who was in a death camp.

“She was angry at her mom for letting this happen,” Jeffrey Scharf said.

She never saw her mother again. But the Soviet Army liberated Gabersdorf in 1945, and Scharf had a second chance at life.

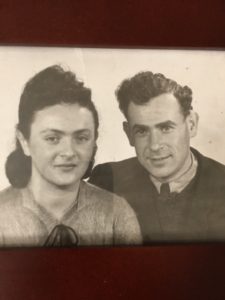

She met her future husband, Bernard Scharf, in a displaced persons camp in 1947. He had fought for the Soviet Army during the war and defended Stalingrad during a crucial battle.

But after the war, he fled Joseph Stalin and communist Russia.

Bernard Scharf had a marketable skill — furring — and uncles who would sponsor his immigration to the United States.

“Furs were very popular after the war,” Jeffrey Scharf said.

The Scharfs moved to the U.S. and learned English by reading signs and listening to people in public. Natalie Scharf worked as a seamstress and Bernard Scharf as a furrier. He eventually opened his own business and gave his family a middle-class life.

“They were great parents,” Jeffrey Scharf said.

And even better grandparents, according to granddaughter Cara Scharf, who often slept over at her grandparents’ house in Northeast Philadelphia. Natalie Scharf cooked for her, took her shopping and brought her to the pool and beach.

“She spoiled me like a grandmother would,” Cara Scharf said.

[email protected]; 215-832-0740