By Toby Tabachnick and Andy Gotlieb

“Jewish Americans in 2020,” Pew’s first deep dive into Jewish life in the U.S. since 2013, paints a picture of a population that is diverse politically and religiously, but for whom, overall, “being Jewish” remains important.

Pew’s newest survey of Jewish Americans was conducted from November 2019 through June 2020, with most of the work completed prior to the pandemic. Its methodology differed from the 2013 survey in that it was conducted online and by mail rather than by phone.

While the 2020 study shows few significant changes in statistics from 2013, it does “clarify” some trends, said Alan Cooperman, director of religion research at Pew Research Center.

“You can get a kind of ‘aha!’ moment out of the survey where it shows you something that, yes, it makes a lot of sense, but you hadn’t been able to crystallize it until that moment when you saw it in the data,” he said.

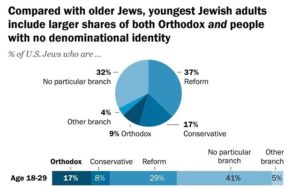

That “aha!” moment came to Cooperman, he said, through the data showing the “religious divergence” of the Jewish population, particularly among young Jewish adults.

The 2020 survey found that younger Jews contain among their ranks “both a higher share who are Orthodox and a higher share who are at the very low end of the religiosity spectrum,” Cooperman said. “If you are familiar with the American-Jewish community, you’ve seen the growth in Orthodox neighborhoods, communities across the country. It’s not surprising, but the survey does capture that.”

In fact, 17% of Jews 18-29 self-identify as Orthodox. At the other end of the spectrum, four in 10 Jewish adults under 30 describe themselves as atheist, agnostic or “nothing in particular,” but still identify as Jewish for ethnic, cultural or family reasons.

Overall, 27% of Jewish adults who have a Jewish parent or were raised Jewish do not identify with Judaism as a religion, the survey found; and younger Jews identify with the religion at a lesser rate than older Jews. While 60% of Jewish adults under 30 identified as “Jewish by religion,” that figure jumped to 84% for Jews 65 and older. Likewise, 37% of Jews under 30 say they are Conservative or Reform, compared to 60% of those 65 and older. Those numbers have not changed significantly since 2013.

Of the three most prominent Jewish denominations, the Conservative movement is experiencing the most attrition. While 67% of people raised Orthodox are still Orthodox, and 66% of those raised Reform are still Reform, just 41 % of those raised Conservative by religion still identify with the Conservative movement as adults. Most of those raised Conservative (93%), however, continue to identify as Jewish.

In general, Jews are less religious than American adults as a whole, Pew found. While 21% of Jews say religion is “very important,” 41% of all U.S. adults say the same. And only 12% of Jews attend services at least once a week, compared to 27% of the general population.

Still, regardless of formal affiliation or religiosity, three-quarters of U.S. Jews say that “being Jewish” is either very or somewhat important to them. Most Jews — 85% — say they feel either “a great deal” or “some” sense of belonging to the Jewish people.

For Jews who rarely, or never, attend synagogue services, Pew asked what was keeping them away. While conventional wisdom has suggested that many Jews do not attend synagogue because they don’t feel welcome or because they cannot afford the dues, the most common reason — given by two-thirds of the Jews surveyed — was “I’m not religious,” and more than half said they are “just not interested” or they have alternate ways to express their Jewishness.

“Part of what Pew is helping us as a community to see is that the problem is apathy,” said Michelle Shain, assistant director of the Center for Communal Research at the Orthodox Union in a call with media. “It’s not that people see a closed door. They see an open door and they aren’t interested in walking through it.”

The lack of synagogue attendance may indicate “religion is not central to the lives of most U.S. Jews,” but Jewish Americans are not, on the whole, apathetic, countered Arielle Levites, managing director of the Collaborative for Applied Studies in Jewish Education at George Washington University and a Philadelphia resident.

“Being Jewish is important to American Jews,” Levites said. “Three-quarters of American Jews are telling us that being Jewish is important, but religion is not important for them.”

Levites, who was on the Pew study’s advisory panel, said one number not in the report was important: Only 2% of Jews never participated in any religious or cultural activities.

“That reflects the durability of the American Jewish story,” she said.

Levites also noted that while various numbers catch the eye, they don’t tell the whole story. And a big chunk of that story is that Jews more than the population at large are happy with their families, health and social lives.

“We would see American Jews as a whole are generally satisfied with the contours of their lives, and that’s not to be taken for granted,” she said, noting that the data was largely collected before the pandemic, so it represents a snapshot of early 2020 more so than spring 2021.

Lindsay Weicher, manager of data analytics for the Jewish Federation of Greater Philadelphia, has worked on the organization’s “Community Portrait: A 2019 Jewish Population Study” from its inception – and continues to analyze the data. She saw a lot of similarities in the reports.

“Overall, a lot of the trends we saw nationally are what we’re seeing local,” she said. “That was validating for us to hear.”

Intermarriage rates in 2020 are similar to those in 2013, Cooperman said, showing “some stability there that some people may not have expected.” While it appears that over the long-term intermarriage rates have risen, there is no evidence in the survey “of any additional rise between 2013 and 2020,” he said. But, “absence of evidence is not necessarily the same thing as evidence of absence. So these are estimates.”

There is almost no intermarriage in the Orthodox community, according to the survey, which found only 2% of Orthodox Jews had a non-Jewish spouse.

Among all Jewish respondents married in the last 10 years, 60% said they have a non-Jewish spouse, while just 18% of Jews married before 1980 have a non-Jewish spouse.

Weicher said the interfaith marriage rates are a bit higher locally than nationally.

Although intermarriage rates have risen dramatically since 1980, Jews under 50 with just one Jewish parent are more likely to describe themselves as Jewish than those over 50 with just one Jewish parent.

“In other words, it appears that the offspring of intermarriages have become increasingly likely to identify as Jewish in adulthood,” according to the Pew report.

Still, children with two Jewish parents are overwhelmingly more likely to be raised Jewish than those of intermarriage. “Intermarried Jews who are currently raising minor children (under 18) in their homes are much less likely to say they are bringing up their children as Jewish by religion (28%) than are Jewish parents who have a Jewish spouse (93%), although many of the intermarried Jews say they are raising their children as partly Jewish by religion or as Jewish aside from religion,” the report states.

Married Jews with one Jewish parent are intermarried at the rate of 82% compared with 34% of those with two Jewish parents. And more Jews say it is important for their future grandchildren to share their political convictions and to carry on their family name than to marry someone who is Jewish (64% to 44%).

Interracial and ethnic intermarriage is rising, according to the report. Twenty-one percent of Jews married between 2010 and 2020 say their spouse has a different race or ethnicity. Among Jews married before 2010, just 1 in 10 or fewer Jews said they had a spouse of a different race or ethnicity.

Pew added a question in its 2020 survey about participation in Chabad activities after “taking heat” for not including a separate question about Chabad in 2013, said Cooperman.

The study found that 16% of Jewish adults in America often or sometimes participate in Chabad programs or services. Of those, 24% are Orthodox, 26% are Conservative, 27% are Reform and 16% are not affiliated with any particular branch.

Other findings in the survey include the political divergence of the American-Jewish population. While 71% of Jews are Democrats or lean Democrat, 75% of Orthodox Jews are Republican or lean Republican.

Almost all Jews (90%) say there’s at least some antisemitism in the U.S., with one third saying they have experienced antisemitic remarks in their presence.

The depth Pew was able to go in exploring antisemitism was valuable, Weicher said. The local report had limitations in questions asked because of sheer length.

“There were some areas they were able to dive a little deeper and get a little more nuance,” she said, adding that the ongoing pandemic impacts will require additional socio-economic research long after the pandemic itself is over.

All in all, the survey offers a good benchmark 1,000-foot view to compare to local data, she said.

“We can go back to local data and re-evaluate what we’re seeing based on this new research,” Weicher said.

Toby Tabachnick is the editor of the Pittsburgh Jewish Chronicle.

[email protected]; 215-832-0797