The first mention of COVID-19 in the Jewish Exponent came on March 3, 2020.

The story combined reporting from JTA with contributions from former staff writer Eric Schucht. In the fifth paragraph in a story about the Israeli elections, Schucht wrote that the final counting had not yet accounted for “the so-called ‘double envelope’ ballots, which include soldiers, hospitalized patients, prisoners and, this year, citizens quarantined over possible exposure to the coronavirus.”

Since that story, the Exponent has published more than 400 articles that mention the word “coronavirus”: op-eds, local news, divrei Torah and more. But even this undersells the impact of the pandemic on our work.

Rare is the story that includes interviews conducted in person or photographs taken by a reporter. Recipes are often selected with our inability to gather with large groups in mind. Most trend stories are COVID-trend stories. Every obituary’s subject was memorialized from afar. Our coverage of a tumultuous presidential election and what was possibly the largest protest movement in the history of the country, according to The New York Times, were handled from home.

The world was fundamentally reshaped by the pandemic, and no aspect of Jewish communal life has gone untouched.

As of March 7, 2021, nearly a fifth of the U.S. population has received at least one dose of a vaccine, according to the Times. For some, the end is finally in sight. Still, the pandemic persists in taking our lives and our time. As the one-year anniversary of Pennsylvania’s work-from-home order approaches, we took inventory of what’s happened.

Ritual Life

In a Feb. 11, 2021, article “Preparing for Purim, Marking a Year of Altered Ritual Life,” staff writer Sophie Panzer looked back to the first Jewish holiday to fall during the pandemic.

“On March 9, 2020, news of the pandemic was making people uneasy, but widespread shutdowns and research about the dangers of gatherings had yet to fully take hold,” Panzer wrote.

Information about the safety of such an event was still muddled then, so some congregations and Jewish groups chose to proceed with caution, while others canceled events altogether. This year, most synagogues hosted their Purim events outside, or via Zoom; only a smattering hosted indoor gatherings.

In 2020, Passover presented the next challenge, and questions about digital literacy became pressing as many families realized that their older relatives could not safely join them in person.

“It’s going to be a much lonelier time for many people,” Rabbi Aaron Gaber of Congregation Brothers of Israel in Newtown said at the time.

As for Shabbat, rabbis reported much higher-than-usual attendance as their congregants learned to use Zoom. On college campuses, Hillels and Chabad Houses tried to unite their students through various versions of “Shabbat to-go boxes” and outdoor meals.

Simchas and daily ritual life faced obstacles too. The eruv maintenance teams that cover massive tracts of Philadelphia rearranged their organization, while weddings, britot milah, b’nai mitzvah, funerals and other occasions were made difficult, if not impossible. Stories about funerals viewed via livestream abounded. Weddings took place in backyards, and britot milah were done as quickly as ritual allowed.

The High Holidays in 2020 left synagogues with few choices, none of them particularly attractive; some, like B’nai Abraham Chabad, chose a radically scaled-down version of in-person services, while others, like Melrose B’nai Israel Emanu-El, filmed or livestreamed their

services.

By the time Chanukah rolled around, outdoor communal activity was frequently restricted to cars. The unstoppable menorah car parade came down the Benjamin Franklin Parkway, and “drive-through” events, to be repeated by many during Purim 2021, were everywhere.

Social Services

The strain put on Jewish social services in Philadelphia was unlike anything faced in recent memory.

It’s not simply that groups like Jewish Family and Children’s Service of Greater Philadelphia or Jewish Relief Agency have more people vying for their services. It’s that those services need to be provided virtually so they don’t pose a risk to the provider. Similar dynamics developed for Federation Housing, the Hebrew Free Loan Society, HIAS PA, JEVS, the Mitzvah Food Program and other social service organizations.

Prior to the pandemic, JRA counted on about 1,000 volunteers to deliver a little more than 3,000 boxes of food to clients each month. As of July 2020, 74 food banks ceased operations entirely and many of them directed their clients to JRA. Now, fewer than 10% of the typical volunteer base is permitted inside JRA’s facilities at any given time. As recently as October, those who were permitted inside were tasked with getting nearly 3,900 boxes of food, household goods and PPE to masked drivers waiting outside the building.

“It’s been very challenging,” said Julie Roat, JRA’s chief of operations in April 2020. Demand has spiked since then.

At JFCS, staff scrambled to move their work online as they brought their clients up to digital speed. Now, the team deals with the typical concerns of their clients — finance, mental health, disability services, eldercare and more — along with a wide variety of COVID-specific issues. Webinars have become a key feature of their work.

Many organizations received outside help, whether in the form of federal Paycheck Protection Program loans or assistance from the Jewish Federation of Greater Philadelphia. Last summer, rabbis were gifted an undisclosed amount of cash, prorated to the size of their congregation, to discreetly disburse to their congregants, as needed.

“This is a very different way in which we are releasing funds into the community,” Abbey Frank, director of program operations at the Jewish Federation, said in June.

School and Education

The first articles about education during the pandemic focused on the novelty. Teachers and students alike found that they had adapted quickly, and social life was re-created, to some extent, through class get-togethers. Students were sleeping in, spared of a commute; teachers like Toby Miller of Kellman Brown Academy were discovering what a mute button could do for a room full of second-graders.

But the novelty wore off and the debate over in-person instruction got heated.

Over the summer, parents, children, administrators and teachers dealt with a complex web of priorities and competing narratives about the safety of returning to in-person education. Some dropped the idea altogether, opting for pod education. As Jewish day schools announced their intention to use the hybrid model, or go fully in-person, enrollment actually went up in some cases.

At public schools, the debate over the return to in-person classes has pitted teacher safety against student mental health and development. Jewish parents were part of an organized opposition to Montgomery County school closures last fall.

“They always say, ‘Follow the science,’” one parent said of the closure. “The school is following the science. So I’ve kind of lost faith in people that want to make those types of decisions.”

On the other side, some teachers have expressed skepticism over the safety precautions taken by their superiors. Thousands of educators, including Jewish teachers, taught outside in freezing weather on Feb. 8 to protest the Philadelphia school district’s reopening plan.

Mental Health

The last year has been a challenge in terms of mental health. According to The Atlantic, “the share of Americans reporting symptoms of anxiety disorder, depressive disorder, or both roughly quadrupled from June 2019 to December 2020.” Isolation remains an issue, especially among the immunocompromised and the elderly.

Last spring, we spoke to mental health professionals who were transitioning their clients to telehealth.

“Even if it’s not in-person, face-to-face interaction,” said David Rosenberg, JFCS senior vice president of programs and strategy, “that telehealth allows us to check in with people and keep them connected and let people know that we’re here and we care about them.”

In the fall, Courtney Owen, JFCS’ director of individual and family services, said that demand for mental health services was high and rising.

Mental health organizations have had to change the way they operate as well.

Tikvah/Advocates for the Jewish Mentally Ill recently held its first online gala. Executive Director Alana Hilsey was pleased with the final product.

“Of course, I want to be there in person and give someone a hug and congratulate people in person and give them physical awards,” Hilsey said. “That part is different. But I think like the sense of community, the essence of Tikvah, that felt the same to me, honestly.”

Relationships

Adults were separated from their elderly parents and grandparents. Those elderly parents and grandparents were separated from everyone for a year. Close friends were unable to see one another, and peripheral friendships were put on hold.

Graduating college students found themselves back in their childhood bedrooms. Recent high school graduates put college off for a year or gutted their way through a dessicated version. Parents who expected to be empty nesters, like Jill Rosen, in Maple Glen, found themselves back in an old role: doing laundry, cooking dinner and keeping house for a whole brood.

“When your kids leave the house, you adjust to them being gone,” Rosen said.

First-time parents had radically different experiences than they’d expected.

Rachel Keiser, who gave birth to her first child, Bradley, in September, has juggled the emotional and physical demands of motherhood with isolation from her friends and family, as well as more time at home with her husband than anticipated.

“It made me love him more, how well he kept me safe and the baby safe,” Keiser said of her husband, Harrison Keiser.

As for social life, some have enjoyed online gatherings as a welcome alternative to freezing outdoor hangs. Ross Weisman, engagement associate at Tribe 12, said that the online events he’s planned for young Jews in their 20s and 30s are generally well-attended and people who join have relished the chance to interrupt their isolation.

“What I’ve been saying since the beginning of the pandemic, and especially as we’re trying to sustain this a year in, is it’s all about the quality of the individual’s experience, not necessarily, like, ‘OK, how many people did we get to sign up for our Zoom webinar tonight?’” Weisman said.

Arts and Culture

Courtesy of Benjamin Behrend

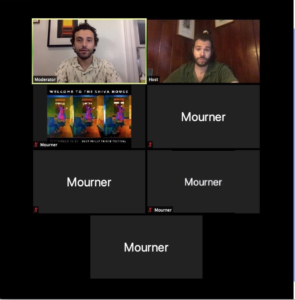

Online culture has flourished, from exhibits at the National Museum of American Jewish History, virtual tours of the Old City Jewish Arts Center and streamed performances from Theatre Ariel. We’ve all become accustomed to Zoom and online streams for cultural events, including movies. Both the Gershman Philadelphia Jewish Film Festival and the Israeli Film Festival of Philadelphia went to a virtual model. Plays, at first adapted for the Zoom screen, started to be written for the medium.

Some artists and performers, like “Pop Art Rabbi” Yitzchok Moully, have continued to make art for people to see in person. Moully’s recurring experiential art piece based in a sukkah, “We All Belong,” was available for a limited number of visitors to the OCJAC back in October.

At NMAJH, frequent public events — movies, lectures, and performance of Jewish music — were bright spots in a difficult year.

“When we can’t get into our intimate theater because a pandemic is passing over us, it’s such a great way to connect, using music,” Dan Samuels, NMAJH’s public programs manager, said in July.

[email protected]; 215-832-0740